Spring 2020

§ Veal Stew, Disappointment

¶ Sophie’s Choice, Styron’s Myth

§ Nickels

¶ “Youth”

§ Frightening and Lugubrious

Δ Sirens, Gratuitous

¶ By a Lake, More Conrad, Novel List

§ “Not a Fabulist”, Brand New Chairman?

¶ Apparatus of Happiness, Playing House

Δ Inception

§ How am I doing? The short answer: there’s a veal stew in the oven, filling the air with the muted but rich fragrance of meat and aromatics simmering in a casserole. (The aromatics are leeks and sage.) I bought the veal at Schaller & Weber; the leeks arrived this afternoon, from Zabar’s. We will get four or more dinners out of the stew, all of them both delicious and effortless — assuming, of course, that the end of the world doesn’t intervene. Right now, anyway, I’m just fine.

Because the stew is best if it sits overnight before the juices are strained for the sauce, we’ll be having macaroni and cheese this evening. John Thorne’s recipe, of course. (He attributed it to Pearl Bailey. — didn’t he? The cookbook will fall apart if I open it.) Actually, I don’t follow the recipe anymore. Just the basic idea: make the sauce with an egg, not a béchamel.

On the other hand, we’re only halfway through April. Because Kathleen just read Sam Wasson’s The Big Goodbye, we watched both Chinatown and The Two Jakes over the weekend, and I found both, under the circumstances, several degrees bleaker — Chinatown, especially. For the first time, I noticed the change of tempo that bubbles up in the orange-grove scene. Until then, the film has proceeded at an almost bewitching adagio, taking the time to lavish attention on its many elegant period details. Thereafter, the gear shifts to più mosso, and the atmosphere becomes hasty. It’s a messy haste, because Jake Gittes isn’t quite clever enough to stay ahead of the bad guys. In The Two Jakes, this haste prevails throughout, telling us more about the director than his leading character, who is — big loss — no longer an insolent, adorable puppy.

I’m heaving through the third quarter of Sophie’s Choice. Something has happened to me since the last time I read it. I don’t like Styron’s verbal flourishes as much as I used to, and sometimes I simply hate them. Just now, I was snagged by “amok flambeau,” meant to be descriptive of New England’s fall foliage, but so little suggestive of New England that it’s jarring to remember that Styron spent so much of his later life in rural Connecticut. Earlier, I choked on Styron’s take on Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony: “inebriate psalm to the flowering globe.” That it actually scans just makes it inexcusable.

Then there are the mistakes. The flutes in Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante K364. (Unthinkable in several ways.) The “main Brooklyn branch of the New York Public Library.” (Brooklyn, once a mighty independent city, has its own library system. So does Queens County, for that matter.) The carelessness of these errors, unimportant in themselves, is emphasized by the tone of documentary exactitude with which we are informed of the horrors of the Holocaust. Every little word counts in this novel, because it constitutes nothing less than the ontology of a major writer.

The other big book that I’m reading is not unrelated, Eric Foner’s Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution. This is “original” Foner study of the subject, and of course I ought to have read it years ago. Even though I’m only just beginning to read about Radical Reconstruction, the book has already shifted the foundations of my thinking about our tragic past. I used to think that the Civil War accomplished, really, nothing. Now I find it hard not to imagine that, left to its Secessionist self, the South — more properly, the “upcountry” Southern yeomen who hated both slavery and blacks — might have organized a Final Solution of their own. (13 April 2020)

§ The veal stew is a disappointment. It’s not very savory. The meat seems to have been terribly overcooked, meaning, paradoxically, that it may have been too good to stew, or at least to stew for as long as it did (following a recipe that has never let me down over thirty years). I’ll freshen up future servings with mushrooms and spring onions, sautéing the first and leaving the latter raw, but the improvement will be just worth the trouble and no more. We won’t starve, but I was counting on a deep satisfaction to make me forget, at least during dinner, this strangely attenuated ordeal.

Attenuated for us, I know. Unlike so many people in the metropolitan area, we are neither sick nor unemployed. I read of an out-of-work nanny who shares a small flat with several other women; they eat one meal a day. Meanwhile, farm produce, for want of distribution, goes to waste. In the space of a few weeks, attempts to thwart the pandemic, which has taken many lives, have upended many more. From us, nothing more than patience seems to be demanded: we have been very lucky.

Perhaps it wasn’t a good idea to read Sophie’s Choice. (14 April 2020)

¶ To read Sophie’s Choice now, in 2020, when the novel is nearly twice as old as its narrator, can’t be a mistake, exactly, but it might be that the time is not right for any kind of assessment. The kind of assessment that I am bound to make is necessarily that of someone who read the book when it was new, or new-ish. What I see now is what I saw then: a big, important novel. The difference is that it was a big, important novel then and now it is the relic of that book. It may have become something else, but I am reminded on every page that this is what seemed important and/or fascinating back in the early Eighties — back when I was in my early thirties. Not only were the themes important — of an ultimate importance, really — but Styron had rigorously observed the commandment to “make it new.” Of the novel’s two principal settings, it was the Brooklyn neighborhood south of Park Slope that seemed exotic, not the Polish locations, and this was a mark of William Styron’s artistry. (Heavens, that a notoriously “Southern” writer had ever gone to Brooklyn otherwise than by taking the wrong subway was intriguing.) There were two kinds of Jews in the book, doomed Europeans and domesticated Americans, and even as background characters they formed very distinct groups. The Jew in the foreground, Nathan Landau, had never been to Europe, much less to a death camp; even odder, the death-camp survivor was a goy. And the narrator was both a Marine Corps veteran of World War II and a virgin, all the way to the climax before the climax. Finally, in a masterstroke that disinfected Sophie’s Choice from the mustiness of once-upon-a-time — 1947, the novel’s year, was all but unsurpassable as a date from ancient history — Styron created a leading man who was not only handsome and brilliant but a pill-popping paranoid schizophrenic.

And of course there is lots and lots and lots of — sex?

I looked up at the ceiling in alarm. The lamp fixture jerked and wobbled like a puppet on a string. Roseate dust sifted down from the plaster, and I half expected the four feet of the bed to come plunging through. It was terrifying — no mere copulatory rite but a tournament, a rumpus, a free-for-all, a Rose Bowl, a jamboree. The diction was in some form of English, garbled and exotically accented, but I had no need to know the words. What resulted was impressionistic. Male and female, the two voices comprised a cheering section, calling out such exhortations as I had never heard. Nor had I ever listened to such goads to better effort — to slacken off, to push on, to go harder, faster, deeper — not such huzzahs over gained first downs, such groans of despair over lost yardage, such shrill advice as to where to put the ball. And I could not have heard it more clearly had I been wearing special earphones. Clear it was, and of heroic length. Unending minutes the struggle seemed to last, and I sat there sighing to myself until it was suddenly over and the participants had gone, literally, to the showers.

Presumably, what Stingo has overheard has very serious reproductive possibilities, but what drifts off the page along with the roseate dust is the impression that sexual congress is best understood, certainly best represented in a work of American literature, as a contact sport. Sport, after all, is far more familiar to men like Stingo than love-making. Love-making is ambiguous; the American boy wants to know: first base, second base, third base, or home? Stingo’s kind of sex has definite rules: there must be throbbing erogenous zones, preferably naked. Penises and pussies and whatnot are itemized, like the commodities on a bill of lading, to make it easier to score — easier for the reader, I hasten to add, to score, qua reader. The fact that young men have hard-ons at the darnedest times, the more inappropriate the better, was the stamp of high-church confessional sex-writing in those days; persistent frustration not only made it “funny” but preserved it from the swamp of pornography. Note, of course, that the frustration is an element of the novel’s historical angle: the writer is quite aware that it has largely evaporated from the atmosphere breathed by twenty year-olds at the time of writing. Sex, in the Seventies, was not only easier to enjoy but permissible to write about. Permit me to fasten on a personal experience of the transition: reading E L Doctorow’s Ragtime (at least as big a hit as Sophie’s Choice) some time after my mother told me that she had enjoyed it, I turned strange colors and fell into syncope upon encountering the word fuck, which I simply could not have imagined my mother’s reading. I suppose it’s quite literally correct to say that America discovered sex in that yeasty decade. (As a perhaps unintentional sign that there remained much to discover in detail, Styron rushes Stingo in and out of a light hangover of doubts about “faggot propensities” in the space of fifteen pages, signaled but not, shall we say, delved into. After all, Styron’s overall point was to insist —however exotically — that sex is not exotic.) Many books of the time celebrate the mere fact of sexuality. Unfortunately for Sophie’s Choice, the novelty has worn off.

Similarly, I feel that there is too much Auschwitz, particularly for the second reading. The great bulk of the material, set in the off-key bourgeois household of the camp’s commandant, Rudolf Höss, could be slimmed down by half at least. (The encounters with the housekeeper, Wilhelmine, and with Emmi, the daughter, well done in themselves, are somewhat de trop, heightening the pile-up of Sophie’s shaming somewhat beyond visibility.) In my view, we have grown beyond the initially natural response of attempting to dismiss the death camps as unspeakable. If nothing else, we know that this is manifestly untrue, that there is always something more to say. Something unspeakable did happen at the camps, over and over again, millions of times, and to get an idea of what that was, or might have been, Karl Ove Knausgaard is wise to steer us toward Paul Celan’s poem, “Engführung.” But that the camps themselves were kinds of factories is a very speakable horror. Their construction was an arguably inevitable outcome of the half-baked pseudoscience that half-educated minds have appropriated from sketchy Enlightenment projects from the revolutionary tumults of the late Eighteenth Century through to the present day (transhumanism?). We don’t begin to know enough about this man-made junk. The most awe-ful book about the Holocaust, in my opinion, is Gitta Sereny’s Into that Darkness, an extended interview that dispenses altogether with Gothic touches on the order of Styron’s white stallion. It is essential to see Auschwitz outside the framework of entertainment — without, that is, exciting the reader’s sympathies and anxieties. Only by stripping away intoxicating excitements can we protect ourselves from somehow, “same but different,” recreating it. (15 April 2020)

¶ What each of the foregoing objections points to is the truly important thing about Sophie’s Choice, which is Styron’s myth, for both are, arguably, excessive distractions from this main event. Styron may have put Sophie in the novel’s title, but the novel’s story is his own. From first to last, Sophie’s Choice tells of the adventure that a callow young Virginian has on his way to becoming a writer, and not just any kind of writer, but a writer of epics. Along the way, he meets a woman whose adventures are considerably more vivid than his own, but nonetheless not epic. Sophie’s story is another kind of tale, a metamorphosis, a transfiguration. At the end, while Stingo, although very much alive, is literally planted in the earth, Sophie is transported to the heavens in a kind of apotheosis, accompanied by her mad lover Nathan. This world is not for her; at the same moment, it finally becomes Stingo’s true home.

Epics are spliced together from travels, and the very first sentence undertakes a journey: “…so I had to move to Brooklyn.” Before we get to Brooklyn, though, we have to know why, money aside, our narrator has to leave Manhattan. (And why he has been in Manhattan.) The problem is that he can’t write there. Possessed by the idea of a novel, a very specific novel that only he can write, he cannot (quoting Gertrude Stein on blocked genius) “pour” the “syrup” Manhattan has been fouled for him in two basic ways. The cubicle in which he sleeps is a sordid hovel from which his only view is of an unattainable Elysian garden. Worse, the job at which he earns his keep is a mockery; it condemns him to write, not the masterpiece aborning within him, but useless summaries of amateur scribblings that will never be punished.

Without being willing quite fully to admit it, I had begun to detest my charade of a job. I was not an editor, but a writer — a writer with the same ardor and soaring wings of the Melville or the Flaubert or the Tolstoy or the Fitzgerald who had the power to rip my heart out and keep a part of it and who each night, separately and together, were summoning me to their incomparable vocation.

This is a summons to travel in a different dimension, no doubt the hardest kind of travel to write about, and, happily, Styron does not waste a lot of time on it. For what is there to say about journeys in words that does not overwrite the battles that the heroic writer fights? The act of writing is doubly indescribable, not only microscopically tedious but, if successful, self-erasing. When the job is done, signs of effort ebb altogether off the page, leaving only an exhausted writer who may feel the need for a stiff drink. And from all his agonizing labor the writer learns nothing, for once again tomorrow his only tool will be trial-and-error. But before the writer can write he must see, and what he must see is that he not only understands nothing but will never understand anything except by capturing this truth, paradoxical as it is, in words. As befits the self-consciously macho enterprise of the heroic writer, work must begin with demolition, and demolition is the true subject of Sophie’s Choice. Sophie’s world is destroyed, of course, but beneath that, so is Stingo’s: a son of the South he may be, but he will never return to live there. Between Stingo and the cozy dream of a backwoods peanut farm lies the impassable rubble of a nightmare. In Manhattan, Stingo knew no one and therefore could learn nothing. In Brooklyn, he meets two larger-than-life figures who lure him through the traps of his own disappointment. These are the adventures that must be completed before he can sit down with pencil and paper — decades later.

It might be amusing, but it would certainly be precious, to map the correspondences of Sophie’s Choice to The Odyssey and The Aeneid. This is not a novel to deconstruct, I think, along the lines of Ulysses. It is enough for the reader to sense the resonance of a great ambition. At the end, the author relays the narrator’s determination “to write about Sophie’s life and death.” But the realization of that ambition is not the only one manifest in the book that we hold in our hand. There is, inextricable from it, the ambition to be capable of telling such a story. My complaint is that Styron’s realization of this deeper ambition is clouded by the indulgence of two of the literary fashions of the time in which Styron wrote. (Or perhaps the problem is that they are not literary fashions.) The hopes that Styron had for the success of his career are expressed many times in Sophie’s Choice — most annoyingly so with the references to Nat Turner, the subject of a book that Stingo would write and that Styron had written. The future of Sophie’s Choice depends, I think, on the reception of the two distractions that I have mentioned. If Styron is lucky, Stingo’s hard-ons will wear down to the unobtrusiveness of Homer’s epithets. (16 April 2020)

§ What, I asked when I had done with Sophie’s Choice, would I read next? Kathleen reminded me that I had mentioned Daniel Deronda as something that I might like to re-read, so I pulled it down from the shelf — an Everyman’s Library edition that had never been opened, as one could tell from the undisturbed placemarking ribbon still folded neatly into the pages.

We talked about the opening scene, set at Baden I presume, in a casino both luxurious and shopworn. This occasioned the sort of repetition of certain previously disclosed truths and previously made remarks that happens in the course of a long marriage when something a little unusual is touched upon, in this case, gambling. Regarding gambling, Kathleen always begins by saying that she has no taste for it. Whatsoever. Whereupon I reply that any inclination to gamble that I might have had was systematically stripped away in childhood, by a bet that I made with my mother when I was about nine or ten.

I say “systematically” because I lost the bet not once but over and over and over again, until and beyond the point at which I thought I might start screaming or sobbing. Instead of which, my soul withered up in exasperation. It was a fine day in early spring, sunny and breezy and really delightful. It was the sort of daffodil day that trumpets the end of winter: we won’t be freezing again for a while. What I had to learn was that this did not mean that summer was icumen in — not yet. But that’s not the lesson that I learned that day. I learned that lesson much later, on a January weekend in Indiana, when it turned out to have been a big mistake to mosey around the quad after lunch in shorts and shirtsleeves, even though it was “almost hot in the sun.” On the earlier day in April, I learned about the horrors of gambling — or at least I thought I did.

It was such a fine day, I said, that every convertible on the road was sure to have its top down. “Nickel a car,” wagered my mother. For the first and last time in my life, I took her up on it.

I don’t remember why my mother and I were in the car. We might have been running an errand to the store, but it turned into more than that — into an occasion for me to keep losing. We pulled out of the driveway and drove up to New Rochelle Road. Traffic wasn’t very heavy. In the short time it took for the car to swing by the club onto Pondfield Road, I yielded to what I knew was an unsporting eagerness to start winning my bet. When the first convertible did appear, and its top was not down, I became all the more impatient for the second to neutralize my loss, which, in the event, it did not. It took a while for this “sunk costs” clutch to give way to outright despair. Until that day, I had enjoyed thinking of myself as a clever fellow who understood the world better than most. But as we neared the village, I lost my innocence and learned that the world can be a cold, cruel place, especially when it is cold, too cold to put the top down. Resisting this part of the lesson, I fastened on the cruelty. How, I wondered, how could the world so resolutely conspire against me? Didn’t everybody know that I was hemorrhaging nickels?

Every convertible in southern Westchester County, its top securely fastened to its windshield, seemed to be patrolling Bronxville that day. The crescendo of drivers who declined to make use of their automobiles’ sexy and expensive feature was like popcorn after a minute in the microwave. Keeping count of my mounting losses went from being difficult to dizzying to sickening. The drive through the village, along Pondfield Road, under the tracks and then Palmer Road, cost me nearly a dollar — and then we turned around and drove home. Please let there be no more convertibles, I prayed. The two convertibles with tops down that we did see (big help!) were loaded with noisy, idiotic teenagers, putting a little extra zest in my mother’s smirk. As I peered into all the other convertibles, I could see only grandmothers.

There’s a difference between gambling and making a really stupid bet. Happily, I was too young, and much too sore, to grasp the difference. (17 April 2020)

¶ Thanks to a piece in the latest London Review of Books (Until I saw the cover, I didn’t know — although Kathleen did — that Britain has been having a toilet-paper situation, too) I rolled the library stepstool over to the fiction bookcase and reached down an old paperback of Joseph Conrad’s “Great Short Works.” Then I stretched out and read “Youth.” I suppose I am old enough now to read about youth without being oppressed by the massive impatience that soured my experience of the state and, for decades afterward, the very thought of it. (Let’s face it: I was born for retirement.) And now that I have read almost all of Conrad’s novels, I am not so sniffy about the “Short Works.” The short works have always fallen into two classes: “The Heart of Darkness” and everything else, with “The Secret Sharer” flickering back and forth between the two, and I have always been more inclined to give the first class another go than to dabble in the second. “The Heart of Darkness,” after all, is one of our central sermons, conjuring all the wickedness of imperialism (especially its soft, rotting, commercial underbelly) in a few pages of intensifying nightmare. But really, a lot of the nightmare owes to Marlow’s tortured telling. I will never understand why young people are made to read “The Heart of Darkness,” especially now that I have swallowed “Youth,” which is a lot more readable and (by the adolescent mind) vastly more comprehensible.

Whether or not I am old enough to read about youth, I am certainly old enough to hear Marlow’s narrative sympathetically even though I’ve shared none of his experiences and would never have wanted to. “The glamor of youth” I think I do understand. If it encouraged the young Marlow to be a hero — a hero of enduring hope — it encouraged me to be a jackass. Item: swimming across St Mary’s Lake at Notre Dame in the middle of a dead-winter night, stripped to my drawers. I achieved this stunt without incident, without a moment’s physical misgivings (or givings-out), but it did occur to me, at the mid-point of the adventure, that I had absolutely no reason to believe that my body was capable of undergoing this quite icy challenge. (I believe that this was the moment in which I sobered up.) But I was brightened, not frightened — by the glamour of youth. But was it glamour? Wasn’t it just stupefying boredom?

Although I suspect I’m the only literate person around who hasn’t read “Youth” before, I’ll say a word about the story. It is the straightforward reminiscence of a maiden voyage in which one damn thing goes wrong after another. Because it is the reminiscence of an old man; the story could just as well have been called “Age,” but you don’t have to be a publisher to see the problems with that. The actual title is richly ironic, too, because the hallmark of youth is its incapacity to foresee a sequel. What must follow, to a mind such as young Marlow’s, can only be a series of further “firsts,” of higher summits conquered. My calling the voyage of the Judea “maiden” is ironic, too, for it is of course the ship’s final one. But in old Marlow’s imaginative hands, it can be squeezed to yield the eager young man’s “first command,” even if all he commanded was a lifeboat. It was also the captain’s first command, a detail that gave me pause. What kind of sailor is promoted to captain at the age of sixty? What kind of owner promotes him? What kind of ship belongs to such an owner? When the time comes to gather up all the salvageable goods “for the underwriters,” before the men row away from the burning wreck, one feels that conscientiousness has been invested in the wrong quarter. Not for the first time, either.

As a light literary exercise, you might undertake to translate Marlow’s well-seasoned tale into the doubtless excruciating language of his younger self. Impossible, really. For the young Marlow, conscious as he might have been of danger, and hungry as he obviously was for glory, really didn’t know what was going on. And of course he had no idea of how it was actually going to come out. Only at the end does the older Marlow capture his younger self’s innocence, when he describes the first glimpse of “the East” that he has carried ever since, as a virtual postcard, the first in a thick collection. (20 April)

§ I do try not to complain — and to be mindful that I have very little to complain about. But for a few weeks now I have felt a budding hope that, when the pandemic is a thing of the past (and assuming that I’m not), I will find another way to start the day than the now awfully venerable one of reading the Times. I have already slowed down on reading The New Yorker. Both of these publications soured long ago, even before 2016, but both have become frightening and lugubrious since March. I take the pandemic seriously, but sensibly: I do not want to read about how the coronavirus attacks the tissues of the body, or mull over the arguable similarities in social dislocation between the Siege of Sarajevo and sheltering at home. I found David Remnick’s suggestion that we might “stumble upon surprising, uncanny moments of familiarity” between what we’re going through here in New York now and Mollie Panter-Downes’s account of the Blitz in her September, 1940 Letter from London to be so irritating that it felt more like an insult. I hope that such instances of mournful grandiosity will be seized on by moral historians as evidence of the intellectual decay that has afflicted the so-called élites in recent decades. (I hope that there will be moral historians.)

The coronavirus epidemic is a terrible thing, and my heart weeps for its many victims, but as with Hurricane Katrina in 2005, it is the wide spread of official dereliction and incompetence that has proximately caused the damage. Neither of these calamities can be properly viewed as a natural disaster; they are the consequences of shocking negligence and carelessness. But this is no time for shock. It is my belief that, so far, by fanning fear, sensationalism, and helplessness, the editors of The New Yorker and The New York Times are as responsible for social anxiety as the politicians who send mixed but self-serving messages. Happily, a sound but reassuring source of local news pops into my mailbox every day, the “eblast” sent out by our state senator, Liz Krueger. I can only hope that you’re half as lucky. (24 April)

Δ The wail of sirens has never been uncommon in this neighborhood. In simple terms, this is the most densely-populated Congressional district in the country, so why shouldn’t there be plenty of emergencies? These days, though, every siren makes one wonder: is the ambulance ferrying an “ordinary suspect,” or a victim of the coronavirus? For a while, it was easy to imagine that the pandemic had taken over all our EMS resources. It was also, sadly, true, because sick people with other complaints (coronary ones especially) were staying away from hospitals just like everybody else. I don’t know how or if that has changed. But at the moment it doesn’t quite go without saying that all the ills to which mortal flesh is heir to have not — unlike so many of my neighbors — left town. The problem is that it is so easy (given one’s lucky ignorance) to interpret the preliminary signs of almost any malady as the first stages of the dread virus.

Which is my way of saying that I was sick on Friday night and Saturday. Now, let me make it clear, for superstitious purposes, that my use of the past tense in the preceding sentence does not imply the boast that my body is not, as I write, in the first grip of the nasty bug. Nor does it mean that I won’t get sick, with whatever it was (intestinal flu?) or with something else, in the coming days, weeks, months, &c. What made the weekend special was that, along with the usual unpleasantness of illness, I had the extra treat of contemplating, hour after long hour, the prospect of “dying alone,” which I put in quotes in order to remind future readers that the two words now constitute a term of art, conjuring up a dark, windowless chamber in which a gasping, perhaps unconscious, probably elderly human being experiences the final hours of existence, with only the occasional health worker looking in now and then. No loved ones. Since moaning and shrieking wouldn’t do any good even if one didn’t feel too lousy to indulge the urge to dramatize, I had no choice but to lie there with a faux-stoic expression on my face while chewing truly foul anxiety. For comic relief, I could now and then ask Kathleen not about our long life together but, “Do you think that symptom x is a sign of coronavirus?” Her unswerving answer, God bless her, was “No.” She even said it sweetly.

By the late afternoon, adding up all the symptoms, which included feeling cold (but not chattering) and warm (but not feverish), plus earlier signs of irregularity in the plumbing (not the ventilation) that I hadn’t noted at the time, I concluded that my plexus was simply on the fritz, due to “worn-out,” and that chills &c and the other thing — I could barely get down a piece of dry toast, from lack of appetite — were nothing more than signs of temporary outage. On Sunday, I felt what nowadays, for me, passes as “fine.” It was only on Monday that I was flattened by the hangover of all that terror.

I’d like to come back, one of these days, to what I had in mind when inserted “in simple terms” into the first sentence of this note. Our Congressional district straddles New York and Queens Counties. I’d like to venture suggestions for “complex terms” that would explain the difference between the Upper East Side (Manhattan coronavirus cases, according to the latest figures: 19,046/1.629,000 population) and Astoria (Queens: 47,511/2.273,000 population). It has more than a little to do with “land use.” (28 April)

Δ Here’s hoping that a week’s silence has caused any alarm. Had I added to this entry, though, I may have done just that. Because — it is too shaming to think of, much less to confess — I gave myself a foot infection. With an old, worn-out slipper. The lining was shot. I couldn’t see the wound, of course, but Kathleen checked it out every night, when she bandaged the other foot, the one that is supposed to get infected (so to speak). She cleaned it and bandaged it and we couldn’t figure out why it kept getting worse until I stuck my hand into the slipper and felt something not unlike a dorsal fin. It was hard, not soft like the eroded sheepskin lining that had covered it. Of course it had hurt, but I hurt all the time for no reason at all. The internist prescribed antibiotics and the slipper (with its mate) was discarded. I think that I have said enough, if not too much. Here, in the middle of all this genuine calamity, I give myself a gratuitous injury, and to make it even worse, don’t know it.

So I’m keeping off my feet even more than I was before, a lockdown (hate that word) within the lockdown. I’ve been reading and writing, but my thoughts on the reading have fluttered with anxiety, and the writing is a tender shoot, not that I would discuss it in any case.

Like everybody else, I suppose, I spend plenty of idle moments wondering what life will be like when and if pandemic conditions come to an end. I can’t help foreseeing a society that is somewhat less open, and I can’t help feeling that this would be a good thing in itself. I believe that one reason why privacy is so challenged today is that, aside from Big-Brother worries, too many people have forgotten what it’s for. Forgotten that it’s about much more than hiding dirty laundry. To be sure, there are some who grasp the virtues of privacy instinctively. But one of the principal purposes of society is to guide those whose instincts aren’t so steady. In my youth, I was certainly such a one. (4 May).

¶ The faults of Edna O’Brien’s House of Splendid Isolation (1994) are obvious long before the last page. A good deal of material in the book does not cohere in the way that all the parts of an admirably-constructed novel do, and the principal characters, particularly the principal character, are at best somewhat flou and at worst “unconvincing.” I’m ashamed to say, though, that none of this mattered to me, not in the least. I read the book with the greatest interest, almost breathless at the big shootout finish. Big shootout finish? Edna O’Brien? What was Edna O’Brien thinking, when she sat down to write a novel about an IRA gunman — more likely a gunman repudiated by the IRA — with a reputation for psychopathy (unmerited, apparently; as mythic as the fairies’) and an old lady in a big neglected house by a lake who falls in love with him? Well, she clearly thought she could do it, that it would be worth giving the idea a try, and I can’t say that she was wrong.

O’Brien makes a virtue of her biggest lapse, which is failing to explain things. She moves, like the killer, too fast for explanations. She does not establish characters before they start talking, and during the brilliantly-constructed sequence of vignettes in the brief first part of the novel, it is often difficult to figure out just what’s going on. But I didn’t mind looking back and clearing things up, because looking back always did clear things up. Our lapsed-Catholic Northern Irish terrorist does not figure in the much longer part that follows, nor in the fourth part’s short-story-like narrative; both of these sections would probably have been removed on technical grounds by a strict editor, with only about a quarter of their contents (perhaps less) worked into the remainder. That fourth part, “A Love Affair,” hangs by the merest thread from the body of the novel, prompted, almost artificially, to disprove a young woman’s caustic dismissal, “Old people know nothing about young love.” And to be sure, the story of young love that follows does not linger in the mind even though it is nicely done. Worse, it blurs our sense of the leading lady even further.

Who is she? Josie O’Grady, first old and then young, a new bride living outside Limerick. But not so young: young Josie has already had a brief career as a housemaid in Brooklyn. Everything about Josie’s marriage borders on the inexplicable; more accurately, the details would be punctiliously elucidated by an English novelist. Where her husband’s family got its money, how he lost it, what drew him to Josie, what allowed her to imagine to think that she was drawn to him; and then, after all that, the curious rapprochement that evidently united the couple after the husband’s spell in Irish rehab (a monastery), leading to a long period, briefly sketched, sometimes just hinted at, during which the big house was put to use hosting parties of sportsmen from across the Irish Sea — the fishing in the lake is excellent — and a later (or is it earlier?) foray into thoroughbred mares, ruinous apparently. Finally, the husband’s death, an episode that links the backstory, again by a thread, to the novel’s present action. The present action begins with the arrival of the gunman, who invites himself to stay in one of the many unused bedrooms while he waits for the opportunity to commit yet another atrocity to mature. Josie, long a recluse by this point, discovers that the terrorist is not a psychopath, and also that she cares for him as she has never cared for anyone else — except for that other hopeless case, the priest in “A Love Affair.” O’Brien doesn’t begin to give us all the information that we would ordinarily demand, but she gives us more than enough to hear heartbeats, and that, as in many old tales, is enough. A biographical portrait would be unwelcome.

Without tales such as this, the Ireland of the Twentieth Century would probably disappear from human recall. It seems that Ireland today has cast off its post-imperial baggage; if it were not for the festering problem of the North, the Republic would appear as sound as any other European democracy. It has overcome both its propensity to internecine violence and its subjection to the policing of the Catholic Church. It appears to have abandoned the undertaking, so bound up with pride and romance, to recreate a Gaelic society, and it speaks English far more clearly than the United States does. Sally Rooney has demonstrated that the repressions that were the making of Edna O’Brien’s literary sensibility have been swept away. Tara French’s novels, like Rooney’s, suggest that Irish writers have left the countryside, with its lakes and small towns and exiguous farms, for Dublin. Nor does emigration exert the imaginative force that it once had: I can feel the intimations of a hole in House of Splendid Isolation where a Brooklyn once story stood. Today, perhaps, O’Brien might have dispensed with the reference altogether; or, consider Colm Tóibín’s Eilis Lacey, who wants to return from Brooklyn, like Josie, but is made to go back. Meanwhile, the novel resonates against two other lakeside stories from long-ago decades, JohnMcGahern’s By the Lake and William Trevor’s Love and Summer. (The latter also features a derelict mansion.) Telling such stories, the Irish writer of the last century dealt from the same deck, which has now been retired. But some of those stories will be read as long as English is intelligible. (5 May)

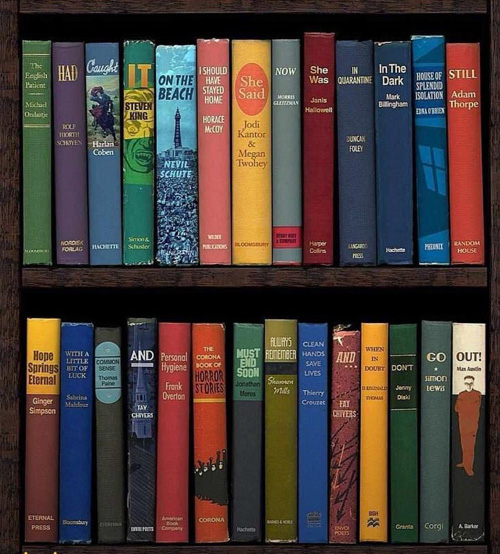

¶ Something that often gets in the way of my writing about books these days is a rather egotistical indecision: I can’t decide whether it’s more interesting to discuss the book, or to chat about why I read it in the first place. House of Splendid Isolation, for example, is a novel that I’d never even heard of until Ray Soleil sent this witty graphic:

That’s all it takes, sometimes, to get me to read something.

With regard to Joseph Conrad, it was the piece by Frederick Jameson in the LRB that I mentioned above. Having read “Youth” for the first time, I thought I’d re-read “The Secret Sharer,” last looked at in school. (Jameson’s actual subject, which I don’t think I named, is “The Shadow Line.” I read it, too.) For all that stuck with me, I might as well not have read “The Secret Sharer” at all. I didn’t like Conrad when I was young, because I hated boys’-own adventure stories, and that was all I could see in him. Do admit, Conrad’s pretty short on interesting women.

Thank goodness, youth isn’t all there is to it. I read “The Secret Sharer” yesterday afternoon, all in one go, with my mouth fairly agape. I have never been so impressed, astonished, startled, even, by Conrad’s prose. The entire story is of a piece, so that copying out an illustrative extract misses the point somewhat. Nevertheless, here are the paragraphs that immediately follow the confession of murder made by an interloper with whom the narrator, newly-appointed the captain of an outbound ship, senses an uncanny rapport:

His care to subdue his voice made it sound monotonous. He rested a hand on the end of the skylight to steady himself with, and all that time did not stir a limb, so far as I could see. “Nice little tale for a quiet tea party,” he concluded in the same tone.

One of my hands, too, rested on the end of the skylight; neither did I stir a limb, so far as I knew. We stood less than a foot from each other. It occurred to me that if old “Bless my soul — you don’t say so” were to put his head up the companion and catch sight of us, he would think he was seeing double, or imagine himself come upon a scene of weird witchcraft; the strange captain having a quiet confabulation by the wheel with his own gray ghost. I became very much concerned to prevent anything of the sort. I heard the other’s soothing undertone.

“My father’s a parson in Norfolk,” it said. Evidently he had forgotten he had told me this important fact before. Truly a nice little tale.

“You had better slip down into my stateroom now,” I said, moving off stealthily. My double followed my movements, our bare feet made no sound; I let him in, closed the door with care, and, after giving a call tot he second mate, returned on deck for my relief.

The physicality of this passage — of the entire story — is radically unlike the physicality that obtrudes elsewhere in Conrad: it portends no violence. It is intimate, or even beyond intimacy. The men are of the same physical and social type. They move, or don’t move, in the same way. They steal barefoot across a deck and down into a cabin. The interloper, we’ve already learned, arrived naked, having swum from the scene of the crime, the ship on which he served as first mate. Later, his new friend, the narrating captain, will be obliged to strip down for a bath while the interloper stands by. And yet the language of identity and closeness is all Conrad’s. The men exchange no friendly remarks, they do not even comment on their complicity in concealing the swimmer from the rest of the crew. As to the crew, they are strangers to the captain. He is variously repelled by his officers, who in turn appear to mistrust him. All of which — the naked swimmer, the hostile crew (to be won over, if at all, in the voyage ahead) — is normal enough as fictional fact. What is unusual about this story is Conrad’s way of writing it. The nakedness, the “limbs,” the bare feet, the extreme intuition are all very unusual. But un-self-consciously so, without any sense of daring.

“The Secret Sharer” is celebrated as an artful allegory — art concealing art — of divided human nature; we are all both captain and murderer, civilized and feral. Twenty years ago, one might have choked on a bit about homoeroticism, which it still seems witless not to mention, if only to dismiss. Eroticism requires objectification at some level, and for this there needs to be another person, even if only an imaginary one. There must be a doer and a done-to. But here we have nothing of the kind. We have, rather, a projected identification that might seem to require the lingo of science fiction to expound. Each man sees in the other his own outer self. The fantasy has nothing to do with lust and everything to do with curiosity: What do I look like to the world? Each man instantly recognizes that the other holds the answer to this question. And that is why the caper succeeds. Without any planning or prompting, each man acts in precise, unpremeditated coordination with the other. At the end, a straw hat floating in the water is the only sign that the captain’s friend, “the secret sharer of my cabin and my thoughts,” has made his escape. They will never meet again, but they don’t need to. (7 May)

¶ Last night, Kathleen and I found ourselves stretched out on the bed talking. Well, I was doing most of it. The thing is, we lay there for about two and a half hours. After a bit of talking about the essay that I’ve been working on, I asked Kathleen if she wanted to read. “I don’t have a book,” she replied. Oh dear. I’ve gone through all the novels that I think she’d like, and ventured to suggest many that I didn’t, but that she did. (Why, you may ask, doesn’t she just eyeball the bookshelves herself? A question that I can’t begin to answer, except to say that perhaps every personal library has its Name of the Rose aspect.) What now? Before I got up to look for something, we spent another hour or so talking about great novelists: who are they? Is there a list? Of course I ought to be able to come up with one off the top of my head, and I did begin one, but it sputtered out after six or seven names. That’s because every name added to a list tends to limit the range from which further names can be selected. Austen, Eliot — I can’t really think of a third name that deserves to follow those two.

nd then there are the novelists with “great” reputations whom I find, well, not. Dostoevsky, for example. Dickens, absolutely — absolutely not great. This is part of the larger problem of male dominance of the field. Roth and Updike: nobody would read them if they weren’t men, and, as their way of being men disappears, no one will read them at all. By this I mean to point to a huge difference between the problems of a male being or becoming a man in any given contemporary society and those of a human being striving to be a person at any time. Not to mention the much more interesting problems of persons trying to get along with each other.

“Proust.” Kathleen mentioned Proust, whom she has never read. I thought back to a recent dip into Lydia Davis’s translation of Swann’s Way. The remembrance of things past was duplicated by my own recollection of reading Proust as a young man. It seemed like all the world then, an endless magic story with a superb finish. Remembering that is much more agreeable than actually following Proust’s paragraphs now, for really it seems clear to my elderly eye that Proust is simply a world-class gossip afflicted with a cynical aesthetic. He is wounded and untrustworthy, and his wisdom is little more than compressed disillusionment. Plus, that huge vocabulary, which so burdens one with shuffling through the dictionary. And, like his sort-of contemporary Edith Wharton, he has a tendency to dwell on difficulties of polite society that turned out to be ephemeral — the indigestion that inevitability followed on the Victorians’ greedy helpings of romantic fantasy and utopian optimism. At best, they write about an awkward phase in the profound alteration of sexual mores from tradition to autonomy.

I would put Trollope on the list of greats, but only on the severe condition that his oeuvre be limited to the two six-novel cycles and a couple of real masterpieces, such as Orley Farm and The Way We Live Now. I loved these books, and I wish that I had stuck to them, and not wandered out onto the fringes, where Trollope’s weak novels disclose — disrobe is the better word — his dreadful fetish with the virginity of nubile maidens, which he deemed lost at the mere acceptance of a proposal of marriage. How I regret the cost of my completist urges vis-à-vis the creator of Lizzie Eustace!

Speaking of completism, I’ve just finished The Little Girls, so now I’ve read all nine of Elizabeth Bowen’s novels. (Wait! According to Wikipedia, there’s a tenth. Oy.) While I enjoyed the bunch, I might just as well have accepted Vivian Gornick’s judgment, in Unfinished Business, which is that there are three must-reads, written in a row in the middle of Bowen’s career: The House in Paris, The Death of the Heart, and The Heat of the Day. These are really good books that align superb writing with gripping characters. The others certainly have their strengths, but they also wear the air of experiments that are only partially successful. The Hotel and To the North are both bothered by Bowen’s attempt to beat off the influence of Aldous Huxley, at least at the start; while The Little Girls and Eva Trout betray exasperation with uncorseted standards. And all the novels, even the best ones, contain chunks of potential short stories, reminding me of Nicola Beauman’s judgment of Elizabeth Taylor’s work: that writing novels was an unfortunate distraction from her true métier.

Which doesn’t get me anywhere, because Kathleen doesn’t read short stories. “They’re like half a sandwich,” I think she said. I don’t at all agree, but I do see how Kathleen likes to settle down with a good book. What’s the use if it’s soon over? (14 May)

§ If my contributions here have dropped off, that’s simply because I find it increasingly necessary to have something to say before beginning to write an entry. I can’t do what worked when I was younger, which was to doodle about a bit off the top of my head, hoping for genuine inspiration. Like everyone else, I’m finding the top of my head to be as empty as Carnegie Hall.

So you ought to be grateful for new issues of the LRB and the NYRB (LXVII/9). The last piece in the NYRB is Joseph O’Neill’s “Brand New Dems?” Then, in this morning’s Times, there appeared Ben Smith’s critical appraisal of Ronan Farrow’s journalism. It’s hard to decide which to address first.

Just as Ben Smith says that Ronan Farrow is “not a fabulist,” so Smith’s piece is not a takedown. It is more in the way of an illumination, confirming tentative judgments that I made long ago, almost immediately, in fact, when Farrow shot to fame abreast the #MeToo movement in 2017. This is not to say that the young man was unknown before then — merely that he was so unknown to me. As someone who doesn’t watch television, I still thought of him as Satchel Allen. (On the photographic evidence — supported by the youth’s mother — “Satchel Sinatra” would appear to be more accurate.) In any case, from out of nowhere, the unforeseen firebrand launched his astonishingly successful attack on Harvey Weinstein. Something about the story seemed too familiar, and I only now realize what it was: see Chapter 17 of 2 Samuel for the story of David and Goliath.

An odd parallel aligns David and Ronan. Both were young, untried men. Not much was known about David was, while too much was known about Ronan — too much of the wrong sort of thing. Surely he was too glamorous to do the grubby work of building a solid case, either as an attorney or as a journalist, against the giant seasoned philistine from Hollywood. The handsome media darling, bearing his embarrassingly rich provenance, hardly seemed cut out to shepherd a flock of ladies through the bruising thicket of technicalities that has for too long protected sexual predators — in short, no more suited to the job than David. But he, too, was victorious. His reporting created a blaze bright enough to light the prosecutors’ way to trials and convictions. Perhaps his provenance, which must account in part for his extraordinarily wide-ranging entrée, was the secret after all. Smith’s report suggests that The New Yorker was dazzled into muting its long-cherished insistence on clear corroboration.

That Harvey Weinstein has been brought down is a good thing; Farrow’s charges may have provided the detonation, but the explosives were far more comprehensively sourced. But the producer’s reversal of fortune triggered Jacobin trials of other well-known men, some guilty of nothing worse than inappropriate goofiness. (I’m thinking of Al Franken.) The air thickened with the stink of opportunistic score-settling. It was all too sensational, too exciting. And the central role of Ronan Farrow’s apparently heroic determination to vindicate the victims of sexual abuse underlined the conclusion that, if men are the perpetrators, they will also have to be the saviors. How much our shining knighthood altered the problematic role of “consent” in abuse cases, however, remains to be seen.

§ Joseph O’Neill‘s profile, as summarized in the “Contributors” listing beneath the NYRB‘s table of contents, mentions nothing more pointed than his membership on the Bard College faculty to suggest that his writing about political affairs might be worth reading — which I must say is disappointing, because his analysis of the fecklessness and folly of the institutional Democratic Party is so brisk and acute that one hopes to discover him in an official position of great influence, party chairman perhaps. Then again, one also feels justified in believing that the institutional Democratic Party has outlived its usefulness by fifty years, that it has not really been a party since LBJ’s volte-face vis-à-vis his party’s Dixiecrat backbone and the ensuing success of Nixon’s Southern Strategy. Instead, it seems to have served as nothing more than a trade association for politicians who don’t subscribe to the essentially anti-political Republican cult. Individual Democrats win elections (when they do) on the strength of their own personal resources, be it the cool charisma of Barack Obama or the fund-raising efficiency of Chuck Schumer. Bill Clinton made hay by running on the Despite-Being-a-Democrat ticket, but this did not work for his vastly less sexy wife.

Since few people otherwise capable of winning an election are either very stupid or very wicked, officials affiliated with the Democratic Party have managed public affairs much better than their opponents, but because active politicians make up only a relatively small part of the population of committed Republicans, it has not fallen on the shoulders of the likes of Dubya or the Donald to articulate coherent party propaganda. The Democratic Party has yet to benefit from the talents of a good Lee Atwater, and successful Democratic presidents have been dogged by charges of failure to advance a genuinely Democratic-Party agenda, whatever that might be. While I agree with just about everything that O’Neill has to say about the urgency of the Democrats’ twinned task of rebranding both their own party and the Republicans’, I think it more likely that building a truly successful Democratic Party will require the armature of an actual human being, yet to be conjured, someone capable of making an intelligent, responsible, and engaging policy presentation. Here, I think, O’Neill overlooks a daunting Republican advantage: stern authoritarians who say mean and frightening things about imaginary dangers are much easier to come by than likable, encouraging, and convincing executives. Obama promised to be one, but in office he displayed, perhaps to his own as well as everyone else’s surprise, a formidably mandarin temperament. I can think of no one who challenged Joe Biden who fits the description, and Biden himself certainly doesn’t. I often wish that the Framers had replaced the age limit with a requirement that presidential candidates complete at least one term of state governorship, but that’s cheating. Still, there would be no harm in the Democratic Party’s adopting such a plank. Proven competence! (A corresponding plank barring mere legislators would be almost as healthy.)

The most obvious way for the Democrats to successfully position themselves, across their many audiences, would be by passing a universally popular piece of legislation that is strongly and durably associated with the party, as Social Security once was.

If you think that that would be hard, let me turn the screw a bit by insisting that the only conceivable such legislation would pivot on regulatory reform. Don’t ask me how anybody could possibly wrest a universally popular program out of regulatory reform, but regulatory reform — legislative reform, really — is what’s needed. What kind of laws our assemblies enact, how they are implemented, and when they are reviewed and updated: these are all questions about democracy that are currently as unstudied as the dark side of the Moon. Perhaps the answer to my conundrum is to run on a (very dangerous) ticket of constitutional amendment.

For the moment, I’ll be happy if Nancy Pelosi commits to memory O’Neill’s ideas of more effective speech. That would be a start. What’s happened to those poor Republicans? Some of my best friends are… (18 May)

¶ The other night, we watched the latest version of Emma: Emma.. We had been on the point of going to see it at the theatre across the street from Bloomingdale’s when the advent of coronavirus made doing so seem like a bad idea; the DVD package has only just been released. I find myself wanting to think about it without judging it, which is very easy to do if I keep my mouth shut. I’m inclined to attribute the film’s shortcomings to the peculiarities of the novel’s structure.

Autumn de Wilde’s take on the story is a very pretty one, almost excessively stylized. Inclined to linger over its own loveliness, the movie runs out of time without making much sense of such important developments as the surreptitious engagement of Frank and Jane. The success of the Box Hill episode owes entirely to Miranda Hart’s very endearing Miss Bates, without whom Johnny Flynn would have an even harder time making Mr Knightley’s speech in a hurry.

It seems that I last read Emma in March, for what must have been the ninth time. I did not begin at the beginning; I began with Chapter 17. If you know the novel well, you may have an idea why. Emma begins with a mounting riot of activity relating to Emma’s scheme to marry Harriet Smith off to Mr Elton. This results in disaster that agitates me more every time I experience it. There they are, Emma and Mr Elton, shut up in a moving carriage, the man just drunk enough to overcome his amatory inhibitions and the lady just astonished enough to mute her outrage. What they share is the conceit of believing themselves to be far too good for the other’s plans — it’s an almost unbearable symmetry. Josh O’Connor, playing Mr Elton, intensifies the drama by exhaling a smarmy whiff of Dracula upon Mr Elton’s leers, and then throwing a little fit when he wants the carriage to stop. He jumps out, and that’s that: we won’t see him again until he returns to Highbury, in Chapter 22, an engaged man. (His dear Augusta won’t show up until Chapter 32. I can’t think of another novel in which a character so vital to the reader’s memory of the tale makes so late a first appearance.) Like an amateur bomb, the climax of Emma appears to have blown up much sooner than expected. By taking up the story at that point, I could see more clearly how Austen works her way through what’s left.

In the meantime, Chapter 18 begins, “Mr Frank Churchill did not come.” Well, of course he does come, but he doesn’t stay. At one point, he runs off to London just to get a haircut, or so he says. He’s a slippery fellow, and Emma can’t make up her mind about him. She decides fairly soon that she doesn’t love him, but perhaps — what’s more interesting — perhaps he loves her? And so the novel swells one way and then the other, like the wake of a boat dissipating among the reeds. Some years ago, there came a time when I had to admit that, even though Emma is my favorite book, nothing much happens in the great middle of it.

Austen’s difficulty, of course, is that her heroine is invulnerable to the slings and arrows of melodrama. She is simply too rich, too accomplished, too pleased with herself. What can happen to her? It’s because nothing can happen that she conjures the Smith-Elton marriage plot out of whole cloth. When that story runs down, it isn’t immediately clear that Austen has anything else to fall back on. Frank comes, and Jane Fairfax comes, and even Mrs Elton comes, but none of them come to any point. All that Emma gets to do is to console Harriet without too abjectly apologizing for having disregarded Mr Knightley’s warnings about the vicar. The things that “happen” — the ball at the Crown, the first “exploring party” to Donwell Abbey, and the second to Box Hill — don’t really happen to Emma herself; rather, it’s she that inexcusably happens, in the form of a thoughtless insult, to Miss Bates. Dramatically, Mr Knightley’s scolding is an event for us, but Emma so completely deserves it that it is not an event for her, but only what she ought to have seen coming, and, but for her vanity, would have done. Nothing at all happens to Emma until the end of Chapter 47, when she realizes, too late perhaps, that Mr Knightley must never marry anyone but herself. This is the one and only risk that Emma encounters in the entire novel, and even if we know the story inside and out we have to congratulate Jane Austen for distracting us from its singular inevitability.

But what kind of accomplishment is that, forestalling all sense of real danger until the very end? No wonder the films can’t get it right.

Although I didn’t much care for Anya Taylor-Joy’s rather babyish voice — it’s a pity that she doesn’t speak with the hauteur of her visage — her Emma haunts me. Coming across a real-life photograph of the actress, I wondered why pretty young women wear makeup of any kind. I can see that girls put it on because they think it makes them look more grown up, but surely nobody over the age of seventeen should labor under the misapprehension that this is a good thing.

The first passage written by Jane Austen to make me laugh out loud was Mrs Elton’s stream-of-consciousness commentary among the strawberry beds at Donwell.

The best fruit in England — everybody’s favourite — always wholesome. These the finest beds and finest sorts. Delightful to gather for oneself — the only way of really enjoying them. Morning decidedly the best time — never tired — every sort good — hautboy infinitely superior — no comparison — the others hardly eatable — hautboys very scarce — chili preferred — white wood finest flavour of all — price of strawberries in London — abundance about. Bristol — Maple Grove — cultivation— beds when to be renewed — gardeners thinking exactly different — no general rule — gardeners never to be put out of their way — delicious fruit — only too rich to be eaten much of — inferior to cherries — currants more refreshing — only objection to gathering strawberries the stooping — glaring sun — tired to death — could bear it no longer — must go and sit in the shade.

But what prepared me to laugh, no doubt, was the phrase with which Austen announced her appearance: “Mrs Elton, in all her apparatus of happiness, her large bonnet and her basket, was very ready to lead the way in gathering, accepting, or talking.” Apparatus of happiness. It’s meant sarcastically, but I can’t help taking it as the best description of Emma itself. (22 May)

¶ About fifteen years ago, perhaps a little more, I surprised a dinner table of very nice people by claiming that Mary McCarthy was the most important American novelist of the Twentieth Century. The eruption of squawked responses indicated that none of my well-read fellow guests would hear of such a thing, though I could tell by the light in the eyes of one or two women that they guessed that it was the sort of thing that Mary McCarthy herself would suggest (although certainly not about herself) — the recommendation, out of the blue, of a writer whom nobody real thought of as a novelist at all and, on the evidence of The Group, surely not a very good one. I can’t claim that the after-dinner conversation was flagging, but it certainly perked up right away, as almost everyone had a better candidate.

I’m of two minds about my rash gesture. What was I thinking? And yet, what else is there to think? Go on, name somebody better. Okay, Saul Bellow — done. But is there anybody else? Fond as I am of William Maxwell, he is an artist of melancholy, of wounded sensibilities, and his most interesting array of characters, appearing in The Chateau, is French. But don’t worry; I’m not going to belabor my point. I just happened to think of it this afternoon as I was reading Chapter 4 of The Group. Here we watch the unlikely marriage of Harald Petersen and Kay Strong, celebrated at the opening of the novel, in the early middle of its unraveling. Kay, of course, would claim that nothing was really wrong, just a bad patch of luck for Harald, but the whiff of tragic doom is already upon her. Tragic, do I say? There I go again. The writing is actually the most peculiarly, sensationally accurate salad of comic domestic misery that I have ever tasted. Just read the passage, comprising the bulk of one paragraph and the whole of the next four, that begins,

Once he had brought one of the authors, and Kay had made the salmon loaf with cream pickle sauce. That would have to be the night they broke for dinner early, and there as quite a wait (“Bake 1 hour,” the recipe went, and Kay usually added fifteen minutes to what the cookbook said), which they had to gloss over with cocktails.

and ends,

Harald knew this, yet so far he had said not a word about the Apartment, which he must have guessed was the thing uppermost in her mind from the moment she opened the door and saw him: what were they going to do? Hadn’t this thought occurred to him too?

Between these sentences, the focus zooms back and forth between the details of making dinner and the grievances of wanting to get life just right, just as it does for anyone confronted by the need to stir up a stew while simmering over the annoyances and shortcomings that could so easily be cleared away if only other people were more thoughtful. Only an experienced cook, by which I mean an experienced human being with years of practice in the kitchen, could have composed this account of discontent in servitude. A more beneficial Vassar mentor would have advised her to stick to her job at Macy’s and sleep around. Even then, though, Kay would have been voted Most Likely to Have the Most Things to Prove. Every home cook is going to suffer stretches of resentment of being unappreciated; what makes Kay’s time in the kitchen really awful is that, naively unsuspecting, she is Playing House. Her heart is not really in the cunning Russel Wright cocktail shaker or the darling little dressing room. Her heart is in advertising these desirable things prominently in the stylish magazine published more than monthly in her mind.

I must say that my decision to re-read The Group was made in the face of reluctance to re-acquaint myself with Chapter 2. It is funny to think so now, but back when the novel was published, in 1963, Chapter 2 brought Mary McCarthy a huge, one might almost say swollen, new audience. The strange thing is that it wasn’t published separately in pamphlet form. I even caught my father reading it, with an air of rank surreptitiousness. (It was thus that I learned the true state of America’s birds and bees.) In Chapter 2, McCarthy author serves a polite cordial concocted from frankly pornographic ingedients. If I didn’t find Chapter 2 sordid this time, it was probably because I haven’t seen Sidney Lumet’s film lately. I wonder what today’s young ladies would make of a college graduate laboring with Dottie’s innocence of s-e-x. A few of them might even be envious. (26 May)

Δ I could bring this entry to a close with some further words about The Group, which I was very sorry to finish re-reading yesterday, or about Zachary Carter’s terrific Price of Peace: Money, Democracy, and the Life of John Maynard Keynes (at last I’ve read something about “marginal utility” that makes a kind of 3D sense — just a hint, but it’s a start), but instead of mumbling about what’s going on in my head, or even in the apartment, I’ll say just a word about what seems to have happened just outside. Our bedroom window looks out onto the patio of a residence for Doe Fund workers that was built into the four-wall shell of an old hotel fifteen or twenty years ago. (From our last apartment, we could look down from the balcony right through all five floors’ worth of empty space.) On holidays, there is often a party on the patio, usually a barbecue, and given the acoustics the evidence of liveliness is somewhat amplified. Never, though, have I heard as much talking and singing as I did this afternoon, an anomaly that I can only explain by reference to the nationwide outbreak of exasperation proximately caused by the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

I could have told you how I’ve been priding myself on resisting the infection of Trump Derangement Syndrome, but since I’m actually worried, for the first time, about the President’s ability to make a very bad situation much, much worse, I’m not sure that I can make that claim. It seems to me now that I was softened up for the malady two nights ago, when Kathleen persuaded me to slip the DVD of Inception into the player. All she remembered from seeing it once before was the spinning top, which somehow caught her curiosity. I remembered a lot more than that, which is why Kathleen had to work to persuade me, but I had certainly not seen Christopher Nolan’s visually unforgettable movie as an alt-right wet dream (excuse my French), depth-charged with an allegory of Deep-State conspiracy theories and fantasies of oligarchic superpowers, all wrapped around a heroically misogynist warning against letting a smart woman into your life (because she will destroy you). Not to mention the endless racket of popguns. Long before Inception came to an end, Kathleen was assuring me that we would never have to watch it again, but when I got up to put the DVD away I was shaken by the feeling that the Donald had been jawboning us at the dining table for two hours while we helplessly despaired of his ever leaving.

Way back at the beginning of this entry, in the middle of April I mentioned that I had started to read Eric Foner’s Reconstruction. As I expected, the book was very well done and yet an awful ordeal to get through. I can’t say that I learned anything really important; I already knew that most Americans, then as now, drew a sharp distinction between the hatred of slavery per se and concern for the welfare of those enslaved. And I still cannot be sure that there was enough real interest in the lives of African Americans to warrant all the upheaval and bloodshed. The only way to avoid dismissing the Civil War as completely futile is to take it as the measure of the many equally tiny baby-sized steps that will have to be made before people of color can wake up every morning in this country without an iota of fear for their personal safety. (31 May)